Even when you are your most pitiful, powerful, frightened or impressive, you are still there with yourself. That’s both the good and the bad news.

Reflections on complexity, inner belonging and meeting myself again and again

Long ago I gave up the illusion that I was a tidy person.

My desk is a revolving reflection of what is floating in and out of my mind.

Piles of disparate books obscure my view most of the time — I may or may not remember why they’re there.

I do know some keep me company for musing, some for meditation or relationships, others have many pages tabbed so I can find a favorite piece of poetry again.

As I write this, I can see the flicker from a terracotta candle, which seems to magically lift my workspace into a flowered meadow.

I have beloved greeting cards propped up against a small desk lamp. And there’s an old jasmine vine, which is now dried and covered in cobwebs and which I can’t bring myself to throw away.

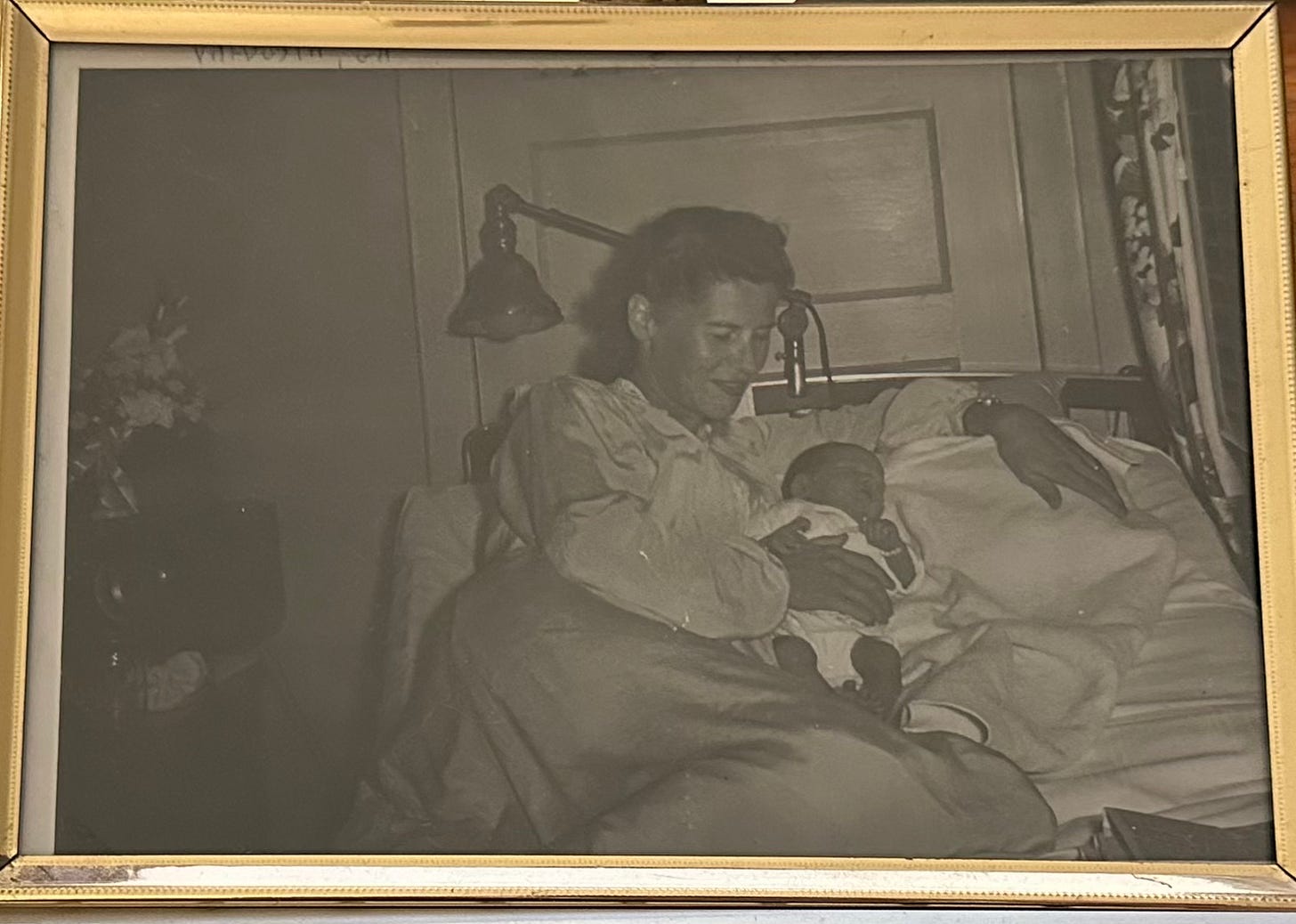

A black-and-white photograph sits at the base of my computer screen — a picture of my grandmother lying on her side in bed as she rests her hand on my father, then a newborn baby.

As much as I love my grandmother, I’ve spent the better part of two decades wrestling with her complexity.

She’s a person who planted in me the seed of what a self-possessed woman could look like. My earliest memories of her are at her vitamin shop. She had a lifelong commitment to health and nutrition, and she joined the first wave of female entrepreneurs before the word was trendy. She used a vitamin company’s MLM model to grow her small shop in Monroe, Louisiana.

I knew her as the person who usually had the good snacks waiting for me when we came to visit. The lady who always had bird and forest sounds playing at night. Whose table side in the living room always had stacks of scientific and clinical journals, and usually some new health-oriented gadget. She is the person who planted the seed in me about what it meant to have a writing voice — Amanda, it doesn’t sound like you. I want to hear from you.

Often I felt my insides pulled in different directions any time I was around her with my family. I knew from the stories told on repeat — she wasn’t a very attentive or gentle mother to my aunt, uncle and father. In my 20s I heard some of these stories in more detail, and they made my stomach curl. And I knew I was being asked to pick sides, away from my grandmother, but I never quite could. Because, you see, my grandmother is also the person who I confided in when I thought I might not ever be someone who goes to church again. She didn’t act shocked or horrified — she said it was no problem. She was person who helped me become familiar with myself as a young adult.

Objectively, I can look back and recognize that, by any conventional standards, my grandmother wasn’t very affectionate; she put pressure on her children in a way that’s hard to quantify. She wanted a tidy ship and meant for things to run according to plan.

In my 20s, I also learned that she and my grandpa — who had a WWII romance via the postal service — never really wanted children. But that they had them anyways “because that’s what you were supposed to do.” The day I learned about this, I felt genuinely sad that they became parents against their true desires. I was also still glad to be alive because of her. I was sad for her pain and grateful in spite of it because I needed her to be my grandmother in this lifetime.

As I retrace her life, I recognize how she fought for her independence while also bearing the weight of so much from society. If there’s anything I’ve learned from my own experiences as a mother, it’s that when the weight of the world is on your shoulders with no relief in sight, you eventually reach a breaking point where you’ll start considering anything — sometimes the unimaginable, most cruel and heart-wrenching things — if it means getting that pressure to lift.

My aunt asked me a few times, “Why doesn’t she seem sorry for what she did to me as a child?”

I never had a good answer for her.

My grandmother remained undeterred in her devotion to her vitamin and health research, even after she sold her small business. She traveled around the country with my grandpa with their RV camper hauled behind the conversion van. She lived a happy life with my grandfather until he died in 2012; she followed him a year later.

I keep her picture next to me so that I never forget that we all have layers inside our stories. And no one can ever know the full truth of what we experience.

***

So, too, do you hold the story of all you have ever been and will become.

You hold the complexity of the universe, even as you let people down or grab a chicken sandwich in the drive thru.

Even when you are your most pitiful, powerful, frightened or impressive, you are still there with yourself.

That’s both the good and the bad news.

With this in mind, I’m using this newsletter as the ground for meeting ourselves exactly as we are. If you are ready to step into your own voice, to face yourself, to uncover who you are infinitely, I invite you to come on this journey. This is the journey I’m on.

Stories like your aunt/ dad’s about their mother always make me worry about how I’m messing up my own kids. 😱

May we all have a grandma redemption arc!

So beautiful, Amanda! I'm in the midst of reading "Women Who Run With the Wolves" for the first time, and so much of what you write here hits the same notes.